Epicurean Wisdom

Until recently I dismissed Epicureanism as just another brand of hedonism. But I’m beginning to see that the Epicureans understood hedonism much better than we do today. On the surface, they present a contradiction: their basic tenet is that the attainment of pleasure and avoidance of pain are the sole purpose of life. And yet they warn against overindulgence:

It is not by an unbroken succession of drinking bouts and of revelry, not by sexual lust, nor the enjoyment of fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul.

- Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

A bait and switch! I was expecting The Wolf of Wall Street, but here Epicurus is telling me to go live in a monastery. Is he interested in maximizing pleasure or not? Maybe the Epicureans were really just “closet Stoics” with a distaste for superstition, and the whole pleasure thing was just a front. But there’s a better explanation, one that reveals a certain wisdom to Epicurean thinking: that they had learned how to maximize pleasure in their lives, and (as usual), we’re the fools.

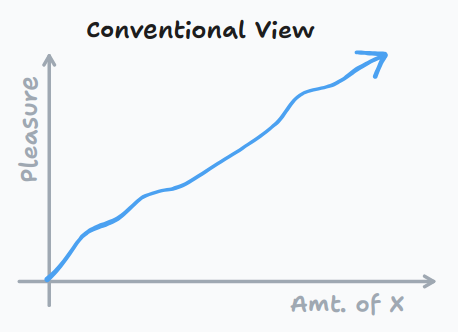

Our naive understanding of pleasure is “monotonic”: the more of X the better. One easy consequences of this view is that pleasure has no maximum. That if one piece of chocolate cake is good then two is better, and three even better; that luxuriating in a hot tub for two hours is better than doing so for only one hour; etc.

We all subconciously understand that this conventional understanding of pleasure is deeply flawed. But we generally fail to appreciate why, and doing so offers some suprising insights. The problem with the monotonic view is simply that the second piece of chocolate cake doesn’t taste as good as the first. The cake might be identical in every regard, but our experience of eating it isn’t a copy of the first. And in order to make the experience identical you’d need to wipe your memory of having eaten the first piece, in which case it wouldn’t really be a second piece. Our desire for a thing needs to be “recharged” before we can fully appreciate it again.

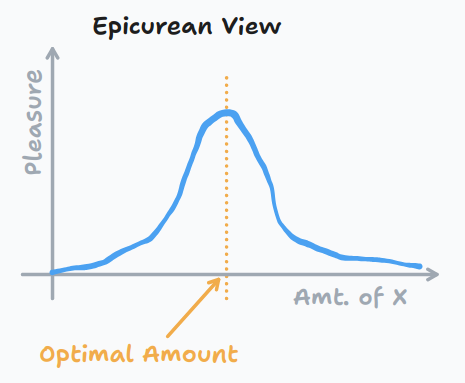

This offers a very different view of pleasure, as something that has a maximum. This means that, at some point, having more of a thing is actually less pleasurable than having less of it. The Epicureans appear to have cultivated a deep understanding of and appreciation for this apparent contradiction.

One suprising consequence of this perspective is that we, in the 21st century, may have already found ways to maximize pleasure in many realms. That with a modest income, you can experience as much pleasure from, say, eating as is humanly possible. And that when we pine for the lives of wealthy celebrities, we’re really asking to be less satisfied than we could be today: if the “most pleasurable dose” of a thing is rather small and available to almost anyone, then having the ability to acquire more is just a harmful temptation.

So under this model, maximizing pleasure requires contemplation (“it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance”). Under the “monotonic” model this isn’t necessary: you don’t need to think, just acquire more and more and more of a thing. The Epicurean view requires us to ask, before reaching out for a thing, “do I really want this, or am I just accustomed to wanting it?”